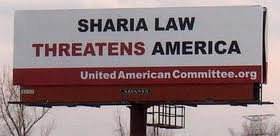

This question has animated scholarly, religious, and political debates for centuries. These debates have been lively, at times contentious, and have been held (under different circumstances and leading to different results) in different parts of the Muslim majority world as well as in parts of the world with few, if any, Muslims. More recently, it seems that the question “What is sharia?” has become a pressing concern in Western countries with growing Muslim minorities who continue to be unevenly incorporated into the imagined image of the “French”, “Swedish”, “German”, or “American” citizen. Central to this uneven incorporation (and at times, explicit discrimination) is the anxiety produced by the supposed relationship between all Muslims, everywhere, and this “universal law” which is said to be incompatible with Western liberal ideals such as women`s rights, gender equality, private property, freedom of speech, the freedom of choice. In addition, sharia is said to be incompatible with what are deemed “civilized” modes of punishment. In the United States today, sharia has become a well known for connoting the word “bad.” National politicians rail on national television broadcasts about the “dangers of sharia”, op-eds are written in well-respected newspapers explaining why sharia is un-American, and wars have been legitimated in part through describing the abuses of sharia. In fact, the images associated with the word sharia demonstrate an understanding that Islamic law is inherently and indigestibly different due to its illiberal and oppressive cosmology. The evidence marshaled to prove this “oppressive” nature of the sharia inevitably centers around the treatment of women and of female bodies within “Islamic Law.” Thus, a google image search of the word “sharia” spits out an assault of pictures of women with burned faces, women behind the bars of a burqa, women being decapitated by bearded men, women being buried and stoned, and images of women (and children, the second most popular category) exposed to all kinds of corporeal violence. These images speak their definitions of sharia; sharia is immoral. Sharia is scary. Sharia is barbaric.

[Has Your State Banned Sharia? Image by Mother Jones]

I am skeptical that when US lawmakers try to “ban” sharia in the United States they know, or care about the intricacies of how different practices of sharia have been formed through the intertwined histories of religions, cultures, economies, and state formations. I don`t think that when potential candidate for the US presidency Herman Cain states that “there is this attempt to gradually ease sharia law and the Muslim faith into our government" he cares that, to anyone who takes the 15 minutes to read wikipedia`s entry on “sharia,” his statement is nonsensical. Denouncing sharia, in this context, has less to do with the sharia itself than it does with domestic politics in the United States and the upcoming US Presidential elections. The fact is that there is no single definition or practice of the word “sharia.” The impossibility of a unified and universal definition is due to many factors, perhaps the most important being that there is no unified and universal practice of Islam, the religion from within which sharia is said to derive. Moreover, like Christianity, Judaism, or Buddhism, Islam is not a transhistorical category of practice. That is, the ways people interpret and practice Islam has changed, and will continue to change within shifting economic, political, and social terrains. Because the histories, languages, cultures and traditions of Southeast Asia, the Indian Subcontinent, Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, and China differ, Muslim religious practices in the states within those regions also differ1. Keeping the trend of willfully ignoring even the most basic facts about Islam, when another potential US presidential candidate, Rick Sanatorum, states that "sharia law is incompatible with American jurisprudence and our Constitution,” I do not think that he is troubled by the vacuity of his words. These politicians’ discussion of sharia has more to do do with American politics, muscular nationalism post 9-11, and the ongoing War on Terror than it does with Islamic law. The United States invaded Afghanistan in part because (the administration said) it was liberating Afghani women from the abuses of sharia. And yet, Saudi Arabia, America’s closest Arab ally, is not only a country where women cannot drive, must wear the chador, cannot travel alone, and are segregated from most aspects of public life, but is the country that is directly implicated in the Taliban`s rule in the name of Islamic law. Even more striking, Saudi Arabia is the country of citizenship of most of the 9-11 bombers, of whom none were Afghani. Despite these facts, Saudi Arabia is never cited as a country whose people need to be rescued by the United States from the ravages of Sharia. So clearly, sharia is compatible enough with American values to allow for a “special relationship” to develop between the United States and Saudi Arabia.1

[US Presidents and Saudi Kings Not Discussing Sharia]

In Lebanon, where I have conducted the majority of my research, sharia is synonymous with personal status law. In this country, often considered one of the most secular Arab states, there are three different laws applied in the different personal status courts for Shia, Sunni, and Druze Muslims. These personal status courts have jurisdiction over marriage, divorce, separation, custody, inheritance, and other matters considered integral to kinship. In matters such as custody and divorce, these Muslim sharia courts (the way they refer to themselves) must “share” jurisdiction with civil courts such as that for the protection of minors and criminal courts that hear claims of spousal abuse, and they must adhere to the code of legal conduct set forth by the state. Thus, there is supposed to be a representative of the attorney general in every Muslim personal status court in Lebanon, and their opinions must be solicited in rulings dealing with divorce. Comparatively, there is no mechanism of state oversight within the Christian personal status courts operating Lebanon, which are much less regulated and operate with much less constraint than their Muslim counterparts. The judges presiding in personal status courts (of all recognized religious sects) are religiously trained; that is, they are not graduates of a government institution, as they are in other neighboring states such as Jordan, where the judges presiding in personal status courts adjudicate a law that was put into effect, and thus can be amended, by the government. Here, as in Iran and unlike in Lebanon, a sharia judge is a graduate of the judges` college, a civil institution. All three of these states (Iran, Jordan, Lebanon) have a different practice of sharia than Saudi Arabia, which (falsely) claims to not have a hybrid legal (civil and religious) system and instead claims that “sharia is the law of the land”. To highlight these differences in tangible terms, Lebanese Sunni personal status courts adjudicate an Ottoman era law that is a page and a half long (and defers to the jurisprudence of Abu Hanifa on issues not covered in this page and a half), while in Jordan sharia courts (which are only Sunni Courts) adjudicate a thick, long, and dense law passed by the Jordanian government and overhauled most recently in 2010. In Saudi Arabia, courts adjudicate the jurisprudence of Ahmad ibn Hanbal (a Sunni jurisprudent), and there is no published and/or legislated “code” that judges (and lawyers) are obliged to follow. Undoubtedly, the Al-Saud`s ceaseless proselytizing of the most draconian interpretation of “sharia” has played a role in the idea that the real sharia is this one rigid thing. But the impossibility of a “one size fits all shari`a” is just as much due to the different histories of Islam as to the different histories of the nation state. What sharia “means” and how it is “practiced” in the context of Saudi Arabia, Iran, Lebanon or Jordan owes just as much, if not more, to the particular histories of those nation states than to some universalist notion of Islam. In fact, even within these states there are different understandings of sharia. Thus, state practices of sharia are often different from the sharia advocated by opposition Islamist groups.

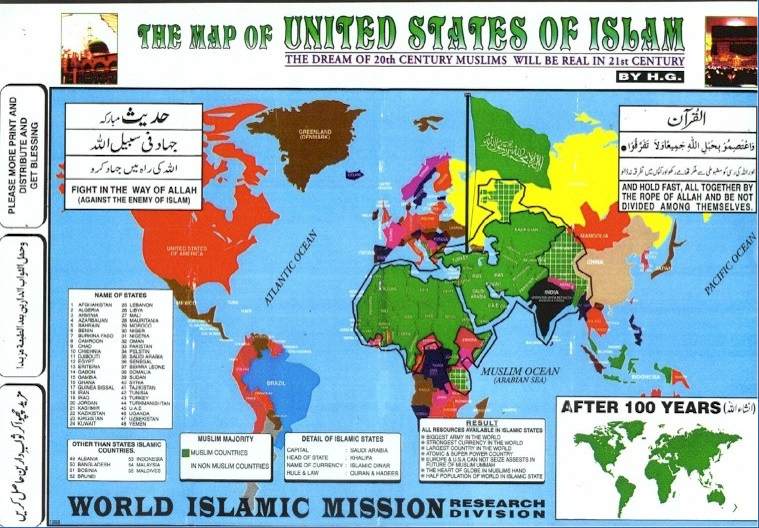

[Fear of a Muslim Planet. Image From Unknown Archive]

Furthermore, one of the fears of sharia touted in the United States is the fact that Islam is an essentially proselytizing religion. And yet, many times I have transited through American airports and stood in awe of bands of eager and bright-eyed teenagers wearing wooden crosses and toting bags destined to some African country. These teenagers move with confidence through airport security, on their way overseas to spread their version of a Christian moral universe. So clearly, proselytizing itself is also not an issue in the US. However, if American airports suddenly witnessed bands of Muslim teenagers with fervent looks, hijabs, skullcaps and Korans on their way to foreign countries I am sure that they would meet scrutiny not only from security officers, but from their fellow passengers and flight officers. One should ask; If Muslim proselytizers threaten our secular paradise, why do Christian proselytizers not threaten our secular paradise? Similarly, Canon law (of both Orthodox and Catholic varieties), in practice in Lebanon as well as many other countries, has just as many aspects to it that are discriminatory towards women as any form of sharia does. But I have never heard a public speech as to the uncivilized and unAmerican nature of Canon law. Is banning the use of contraceptives, abortions, and divorce also not antithetical to the American women`s rights movement? One could go through a list of examples that demonstrate how the word “sharia” occupies a special place in the political and social imagining of the United States. The word seems to index, to put it perhaps too simply, danger. Public Koran-burning parties, a vitriolic campaign to stop the building of a interfaith center near ground zero, and the introduction of legislation to “ban sharia” in 15 out of the 50 states that make up these United States must be understood within a lexicon of the War on Terror, of racialized and indigestible difference, and of xenophobia.

So what is sharia? It is, in its most bland definition, the moral cosmology that is meant to saturate and legislate shared life in Muslim communities. In the Lebanese state, the sharia is the muslim personal status laws, in Iran it is the spirit and much of the content of the legal system, in Saudi Arabia it is what the state says it is, and in the minds of many Islamists throughout the world, it is the utopia that their struggle promises. It is a word that is cited by a Yemeni President to try to prop up his teetering regime, a word that was cited by an American President in order to foster support for a foreign invasion, and a word has been cited in Egypt and in Afghanistan to both promote and prohibit educating women. It is a word that conjures up, in the minds of some, promises of justice, gender equity, and social harmony. In the minds of others, it conjures up images of bearded men flogging adulterous women, hanging homosexuals, and marrying children. For some, it is the law of God, for others it is the law of man trying to live within God`s imperatives. For many, it is a body of jurisprudence that can be studied, appreciated and critiqued. It is many things in theory, and still more in practice. But unfortunately, today in the United States, sharia is little more than a scare tactic.

1. In fact, despite the fact that most people seem to believe that “Islam” and “Arab” are married terms, only 15 percent of the world`s Muslims are Arab. There are more Muslims in Ethiopia than there are in Saudi Arabia, as many Muslims in China as there are in Yemen, and more Muslims living in the Indian subcontinent than there are Arabs in the world, period.

![[Sharia For Dummies. Image From Unknown Archive]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/sharia_dummies.jpg)